Education is an investment in the future. Since World War II the nation’s economic growth through Human Capital has been driven by the increased productivity and numbers of college educated workers.

Until 2010 the United States had steadily and substantially increased its annual investment effort in higher education. But in 2011 this reversed, and since then the country has steadily and substantially reduced its annual investment effort in higher education and its future.

By 2022 the national investment effort in higher education was just three-quarters of what it had been in 2010. Compared to the 2010, the 2022 annual investment effort was $135.8 billion less.

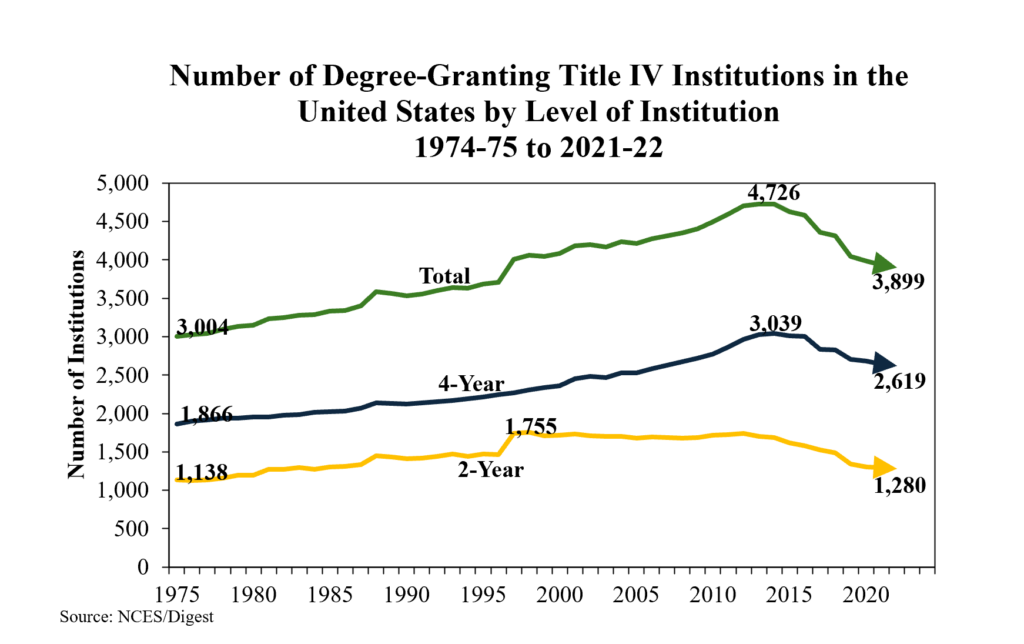

The sharp reduction in investment effort in higher education has produced a long list of consequences for higher education institutions. Recent headlines have reported: program closings, campus closings, mergers, budget holes and gaps, cash strapped, shortfalls, credit downgrades, system reorganizations, pay cuts, deferred maintenance, faculty layoffs and faculty buyouts.

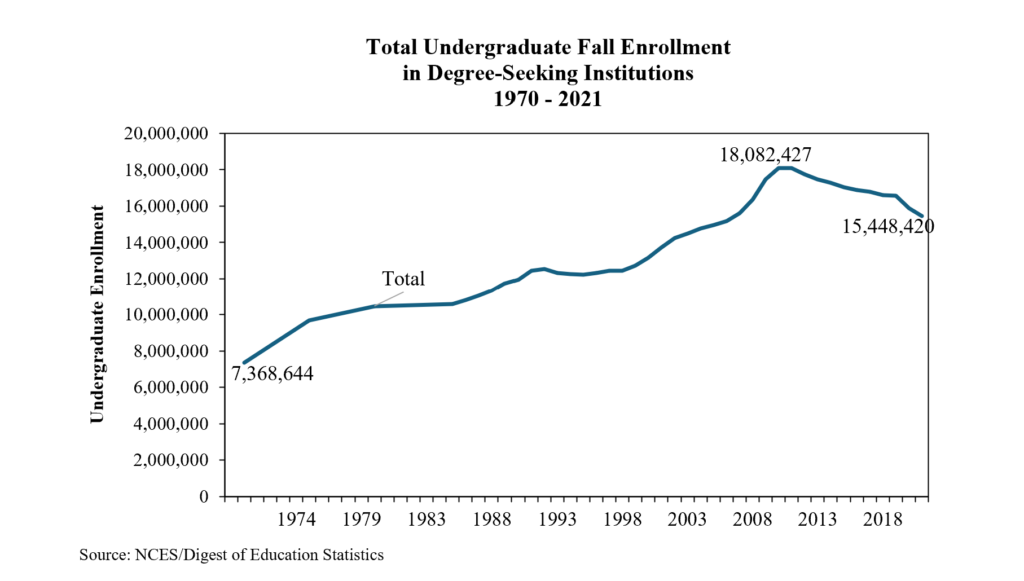

The disinvestment in higher education has had it’s most dramatic effects on undergraduate student enrollment—in whom the higher education investment is made. Undergraduate student enrollment grew steadily and substantially from 7.4 million in 1970 to a peak of 18.1 million in 2010. Thereafter, enrollment has declined to 15.4 million students by 2021.

The undergraduate enrollment decline between 2010 and 2021 was 2.6 million students. When this total is disaggregated by the income levels of students, the number of undergraduates with federal Pell Grants (for students from low-income backgrounds) decreased by 3.0 million students, or by -33.0%. The number of undergraduates without Pell Grants (affluent) increased by 0.8 million students, or +8.8%. The decline in enrollment is limited exclusively to students from lower income backgrounds.

In 2010 the National Center for Education Statistics projected that undergraduate enrollment would continue to increase from 18.1 million to 20.6 million undergraduate students by 2021. Instead enrollment dell to 15.4 million undergraduates. By 2021 there were 5.1 million fewer students enrolled than had been projected a decade earlier. Actual enrollments were about three-quarters of what they had been expected to be.

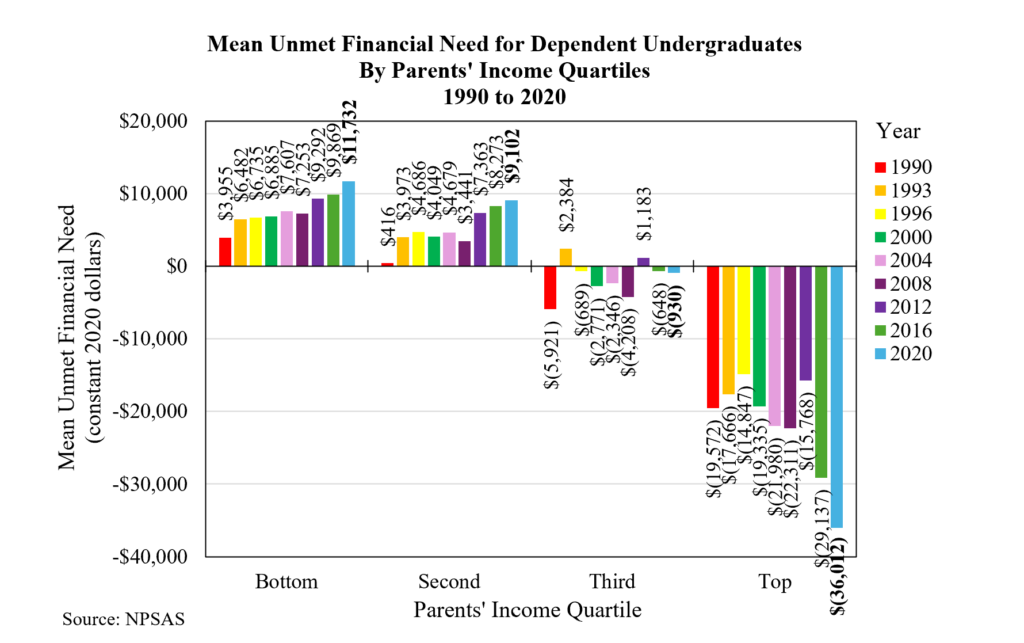

Data collected in the National Postsecondary Student Aid Study (NPSAS) between 1990 and 2020 explains why only students from lower income backgrounds have turned away from higher education since 2010. We have analyzed NPSAS data on college affordability across quartiles of family income to measure financial barriers to college enrollment. Unmet financial need is the difference between the costs of college attendance and the sum of family and financial air resources to pay those costs.

- In the bottom quartile of family income ($0 to $37,000), average unmet financial need grew from $3955 in 1990 to $11,732 in 2020 (constant dollars).

- In the second quartile of family income, ($37,000 to $83,000), average unmet financial need increased from $416 in 1990 to $9102 in 2020.

- In the third quartile of family income ($83,000 to $146,000), there was no unmet financial need.

- In the top quartile of family income (above $146,000), family resources vastly exceeded average costs of college attendance.

Education is an investment in the future. The sharp reduction in the higher education investment effort since 2010 will inevitably diminish he country’s economic future. Early signs that this has already begun to produce predicted consequences are beginning to appear in data produced by the Census Bureau:

- The share of the workforce with a bachelor’s degree or more peaked in 2020 and has declined in the two subsequent years.

- The share of earned income from workers with bachelor’s degrees or more peaked in 2020 and has declined in the two subsequent years.

To reverse these trends and secure a prosperous future, increased investment in higher education is essential. Stakeholders, policymakers, and the public must work together to advocate for the necessary funding and support to bolster our nation’s educational institutions and students.